Schmidt said he well understood why Caravaggio would appeal to someone like me, an incurious American toddler nursed on the teats of an illiterate culture. He sympathized with my need for signposts and symbolism, because, being an American, he’d said, I couldn’t help myself, being an American, he hastened to add, I’d been stunted and impaired and because of this geographical shortcoming I suffered a lack of nutrients readily found in the ancient soils of Europe, Austria especially, its soil as dark and rich and awash with history as one could ever dream of, the complete inverse of the anemic American soil on which I’d regrettably been raised, he’d said, a wasteland, he’d called it, a revolting abyss, he’d added, a nation whose ground was utterly devoid of nutritional benefits, bereft of any sustenance at all, a dirt no doubt replete with candy wrappers and condoms and the residue of all manner of crimes, but not art, not history, not the fundamental ingredients required for the temperament of an important critic.

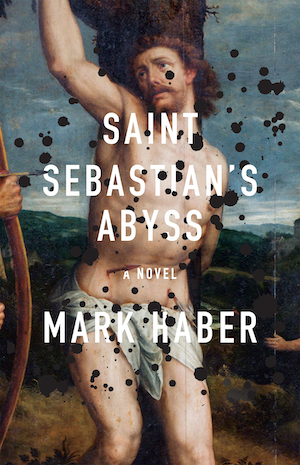

Mark Haber: Saint Sebastian’s Abyss, Minneapolis: Coffee House Press 2022, S. 23.